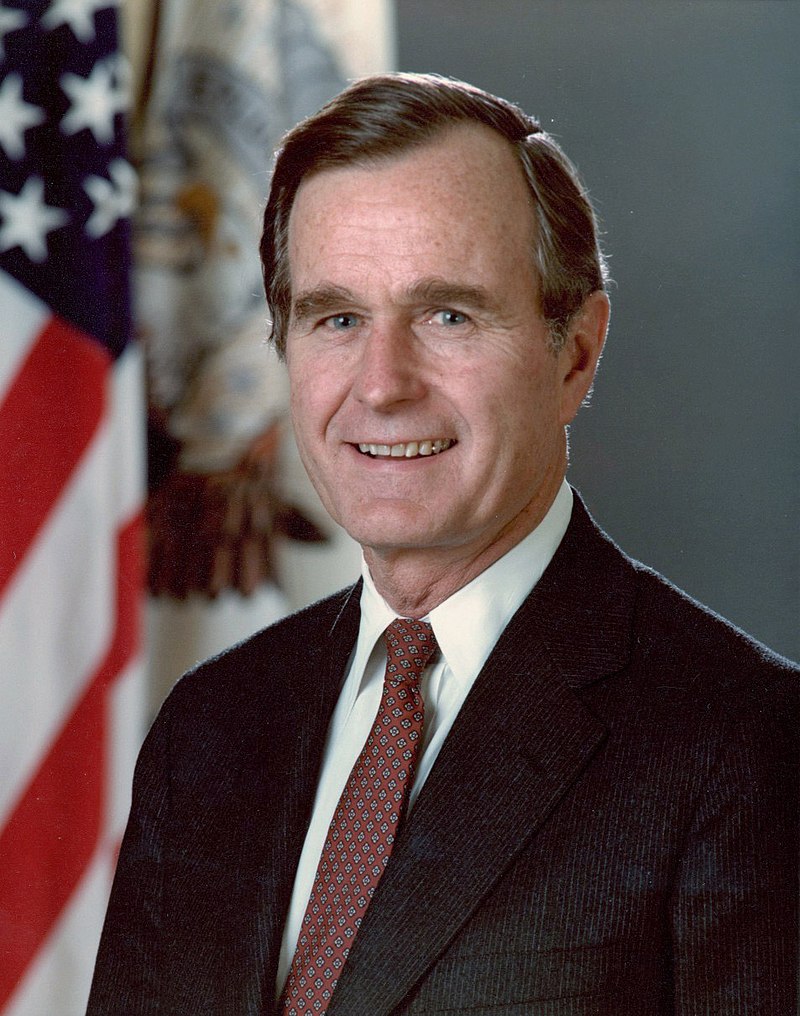

In the days after the passing of George H. W. Bush, the nation has remembered his decency, his devotion to family and friends, his courageous military service, his awkward rhetoric and, above all, his prudence. All were elements in a long life and a distinguished political career.

But as a student of the American presidency, I worry that our popular impressions of presidents can be superficial and incomplete. Like all of us, presidents are complicated people, and they don’t always say or do what is expected. Maybe we would do a better job of honoring their memory if we recalled the occasions when they acted against the grain of their public image.

President Bush famously said that he lacked “the vision thing;” and it’s true that he rarely gave visionary speeches. But think for a moment about German reunification. Bush didn’t make the revolutions in Eastern Europe and, like everyone else, was surprised by how quickly and peacefully change came to the nations behind the Iron Curtain. But once those changes were underway, President Bush made an early and complete commitment to the rapid reunification of the two Germanys.

He insisted that reunification could take place without compromising German membership in the NATO alliance and the European Community. He was confident that the post-World War II economic progress and the democratic experience of West Germany had put historic fears of German nationalism behind us. In holding these views Bush was at odds with foreign policy experts, our European allies and Mikhail Gorbachev—the visionary leader of the Soviet Union.

Bush solidified his relationship with Helmut Kohl, then worked to facilitate a quick and complete German reunification. Along the way he pushed for a new NATO alliance strategy that responded to realities at the end of the Cold War. These were huge accomplishments that could easily have gone off track with hesitation or confusion at any number of pivot points. The president clearly saw where he wanted to go and got there. German reunification was a “thing” that required “vision.”

What about prudence?

George Bush was modest and prudent in his public persona. He rarely took credit for accomplishments and famously kept a low profile in dramatic days like those following the collapse of the Berlin Wall. But from time to time he also made bold moves. On three occasions he sent US forces into combat—Panama, Iraq and Somalia. For all three he was given options on the size of the US military commitment. He always picked the biggest stick.

The intervention in Panama could have been limited to the capture of Manuel Noriega, but that would have left Panama’s corrupt defense forces in power. Bush went for a large invasion that broke the back of the Noriega regime and put a democratically elected president in office.

In Somalia, there were easy steps for the United States to take late in 1992. We could have increased airlifted aid or provided logistical support to UN forces moving to the Horn of Africa. Bush rejected the easy options. Instead, he sent American military personnel because they could get there sooner, end the chaos-caused starvation and save more lives. And he did this as a defeated lame duck president.

For the war in Iraq, Bush made a decisive decision in October of 1990 doubling the US military deployment in the Persian Gulf from 250,000 to half a million. He made the decision on his own authority, without congressional consultation. A force that large could not be sustained for long and would have to be used in a few months or drawn down to reduce the strains of duty overseas. That decision put the US on a countdown to war with Saddam Hussein that could only be stopped by a voluntary Iraqi withdrawal from Kuwait—a withdrawal that never came.

Bush made his Iraq decision in the same month that he compromised with Democrats over budgets, deficits, debt and taxes. The twin decisions would reverse the Iraqi conquest of Kuwait and threaten Bush’s hopes for reelection. They were made within days of each other.

If you stretch the meaning of prudence, you could say that in the fall of 1990 George Bush acted wisely to address a crisis in national finance and another in Middle East security. But at the time, the Bush decisions were seen as controversial, consequential and dramatic.

Richard Nixon once observed that when you least expect it, George Bush “makes the big play.” That was a trait that Nixon admired. In our memorials to George H. W. Bush, let’s remember a few of those big plays and the days when President Bush did things that were not prudent.

This essay was published by The Virginian-Pilot on December 9, 2018